Unit 2 | Aristotle's Argument for Hylomorphism

2.1 | A Puzzle About Coming to Be

Physics 1.1, 185a13–20 (Hardie and Gaye tr.)

We, on the other hand, must take for granted that the things that exist by nature are, either all or some of them, in motion—which is indeed made plain by induction. Moreover, no one is bound to solve every kind of difficulty that may be [15] raised, but only as many as are drawn falsely from the principles of the science: it is not our business to refute those that do not arise in this way; just as it is the duty of the geometer to refute the squaring of the circle by means of segments, but it is not his duty to refute Antiphon’s proof. At the same time the holders of the theory of which we are speaking do incidentally raise physical questions, though nature is not their subject; so it will perhaps be as well to spend a few words on them, especially as [20] the inquiry is not without scientific interest.

Physics I is devote to the subject of “principles” (archai pl., archē) of natural science.

- Archē

- beginning, origin, source (e.g. of motion)

Principle is one

Either motionless…

-

Parmenides

[F8 ] . . . Only one tale is left of the way: that it is; and on this are posted very many signs, that [i] what-is is ungenerated and imperishable, [ii] a whole of one kind, [iii] unperturbed and [iv] complete. [i] Never was it, nor shall it be, since it now is, all together, one, continuous. For what birth would you seek of it? Where [or: how] , whence did it grow? Not from what-is-not will I allow you to say or to think; for it is not sayable or thinkable that it is not. And what need would have stirred it later or earlier, starting from nothing, to grow? Thus it must be completely or not at all. Nor ever from what-is-not will the strength of faith allow anything to come to be beside it. Wherefore neither to come to be nor to perish did Justice permit it by loosening its shackles, but she holds it fast. And the decision concerning these things comes to this: it is or it is not. Thus the decision is made, as is necessary, to leave the one way unthought, unnamed - for it is not a true way - the other to be and to be true. And how would what-is be hereafter? How would it have come to be? For if it has come to be, it is not, and similarly if it is ever about ro k Thus coming to be is quenched and perishing unheard of. [ii] Nor is it divisible, since it is all alike, nor is there any more here, which would keep it from holding together, nor any less, but it is all full of what-is. Thus it is all continuous, for what-is cleaves to what-is. [iii] Further, motionless in the limits of great bonds it is without starting and stopping, since coming to be and perishing wandered very far away, and true faith banished them. Remaining the same in the same by itself it lies and thus it remains steadfast there; for mighty Necessity holds it in the bonds of a limit, which confines it round about. [iv] Wherefore it is not right for what-is to be incomplete; for it is not needy; if it were' it would lack everything. The same thing is for thinking and is wherefore there is thought. For not without what-is, to which it is directed, will you find thought. For nothing else < either> i s nor shall be beside what-is, since Fate shackled it

-

Melissus

What-is (the principle) is one, and motionless, but infinite.

… Or in motion (“physicists”, phusiologoi)

- Thales (everything is generated from water)

- Anaximenes (everything is generated from air, though condensation and rarifaction)

- Heraclitus (everything is fire)

Principles are more than one

Anaximander

All things come from to apeiron (lit., the unbounded)

Empedocles

-

One: the cosmos is in an eternal cycle of combination and separation, governed by the contrary principles Love and Strife

-

Many: everything comes about from the combination and separation of the four “roots”, earth, air, fire, and water, by Love and Strife

[F20] I shall speak a double tale: at one time they grew to be one alone from many, at another time it grew apart to be many from one. Double is the birth of mortal things, and double the demise; for the confluence of all things begets and destroys the one [generation] , while the other in turn, having been nurtured while things were growing apart, fled away. And these things never cease continually alternating, at one time all coming together into one by Love, at another time each being borne apart by the enmity of Strife.

Anaxagoras

[F15] Everything else has a portion of everything, but mind is boundless, autonomous, and mixed with no object, but it is alone all by itself. If it were not by itself, but had been mixed with something else, it would have a portion of all objects, if it had been mixed with any; for there is a portion of everything in everything, as I said earlier [F12]. And the things mixed with it would hinder it from ruling any object in the way it does when it is alone by itself. For it is the finest of all objects and the purest, and it exercises complete oversight over everything and prevails above all. And all things that have soul, both the larger and the smaller, these does mind rule. And of the whole revolution did mind take control, so that it revolved in the beginning. And first it began from a small revolution, now it is revolving more, and it will revolve still more. And things mixed together, things separated, and things segregated, all these did mind comprehend. And the kinds of things that were to be - such as were but now are not, all that now are, and such as will be - all these did mind set in order, as well as this revolution, with which the stars, the sun, the moon, the air, and the aether which were being separated now revolve. For this revolution made things separate. And from the rare is separated the dense, from the cold the hot, from the dark the bright, and from the wet the dry. But there are many portions of many things. And nothing is completely separated nor segregated the one from the other except mind. Mind is all alike, both the larger and the smaller. No other thing is like anything else, but each one is and was most manifestly those things of which it has the most.

Preliminary Results: Physics 1.5–6

-

Coming-to-be is always between contraries.

-

Hence, the number of the principles cannot be one, since there is no contrary to one…

-

So the principles are either two or three, “but whether two or three is a question of considerable difficulty”.

:EXPORT_FILE_NAME: unit2

2.2 | A Solution to the Puzzles

Physics 1.7

-

Aim of the chapter: to establish “the number and nature of the principles” of coming to be (to genēsthai).

-

How? By analyzing the different ways in which things are said to come to be.

Analysis of Coming-to-Be

Physics 1.7, 189b32–34 (Hardie and Gaye tr.)

We say that ‘one thing comes to be from another thing, and something from something different', in the case both of simple and of complex things.

-

A. distinguishes 3 ways of characterizing a single episode of coming to be.

-

“Socrates (the human being) becomes musical”

-

“That which is not musical becomes musical”

-

“Non-musical Socrates becomes musical Socrates”

-

-

First Pass:

-

In (1) and (2), both “that which becomes” and “what it becomes” are simple.

-

In (3), both “that which becomes” and “what it becomes” are complex (or combined, sunkeitai)

-

| “That Which Becomes” | “What It Becomes” | |

|---|---|---|

| Simple | Socrates | Musical |

| Simple | The Non-Musical | Musical |

| “Combined” | Non-Musical Socrates | Musical Socrates |

- Simple cases, in detail:

Physics 1.7, 190a9–13 (Hardie and Gaye tr.)

When a simple thing is said to become something, in one case it survives [10] through the process, in the other it does not. For the man remains a man and is such even when he becomes musical, whereas what is not musical or is unmusical does not survive, either simply or combined with the subject.

- Question

- In which simple case of coming-to-be does “that which becomes” survive (lit., “remain, persist”; hupomenon)?

Answer: - Socrates survives coming to be musical.

- **The Non-Musical** does not survive coming to be musical.

Two Conditions on Coming to Be

Physics 1.7, 190a13–21 (Hardie and Gaye tr.)

These distinctions drawn, one can gather from surveying the various cases of becoming in the way we are describing that there must always be an underlying [15] something, namely that which becomes, and that this, though always one numerically, in form at least is not one. (By ‘in form’ I mean the same as ‘in account’.)…

One part survives, the other does not: what is not an opposite survives (for the man survives), but [20] not-musical or unmusical does not survive, nor does the compound of the two, namely the unmusical man.

- Subject Condition (SC)

- In every case of coming to be, there must be some underlying subject, s, such that it is true ‘s comes to be…’.

- Persistance Condition (PC)

- In every case of coming to be, the underlying subject must remain one in number, although not one in form or logos.

- Cf. Aristotle’s account of numerical unity in Metaphysics Δ:

Metaphysics Δ 6, 1017a30–34 (Ross tr.)

Again, some things are one in number, others in species, others in genus, others by analogy; in number those whose matter is one, in species [= form] those whose formula is one, in genus those to which the same figure of predication applies, by analogy those which are related as a third thing is to a fourth.

Varieties of Coming to Be

Things are said to come to be in different ways. In some cases we do not use the expression ‘come to be’, but ‘come to be so-and-so’. Only substances are said to come to be without qualification.

- Qualified Coming to Be

- s comes to be F (for some predicable F in a non-substance category)

- Unqualified Coming to Be

- s comes to be (or: s comes to be an F, for some kind of substance F)

Applying SC and PC

- Subject Condition applies to both qualified and unqualified coming to be.

Physics 1.7, 190a33–b5 (Hardie and Gaye tr.)

Now in all cases other than substance it is plain that there must be something underlying, namely, that which becomes. For when a thing comes to be of such a quantity or quality or in such a relation, time, or place, a subject is always [35] presupposed, since substance alone is not predicated of another subject, but everything else of substance.

But that substances too, and anything that can be said to be without [190 b 1] qualification, come to be from some underlying thing, will appear on examination. For we find in every case something that underlies from which proceeds that which comes to be; for instance, animals and plants from seed.

- Question

- What about PC?

- Qualified Coming to Be: Of course! It is the substance, or tode ti:

Physics 1.7, 190b24–28 (Hardie and Gaye tr.)

Now the subject is one numerically, though it is two in form. (For there is the man, the gold—in general, the countable matter; for it is more of the nature of a [25] ‘this’, and what comes to be does not come from it accidentally; the privation, on the other hand, and the contrariety are accidental.)

- Unqualified Coming to Be

- The “matter” of substance/subject of unqualified coming to be is knowable on analogy to the matter of qualified comings to be:

Physics 1.7, 191a9–12 (Hardie and Gaye tr.)

The underlying nature can be known by analogy. For as the bronze is to the [10] statue, the wood to the bed, or the matter and the formless before receiving form to any thing which has form, so is the underlying nature to substance, i.e. the ‘this’ or existent.

- Initial formulation of matter:

Physics 1.9, 192a31–33 (Hardie and Gaye tr.)

For my definition of matter is just this—the primary substratum of each thing, from which it comes to be, and which persists in the result, not accidentally.

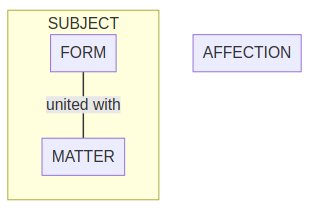

Resolution to the Puzzle

- All coming to be is complex in that which comes to be:

Physics 1.7, 190b11–15 (Hardie and Gaye tr.)

Thus, from what has been said, whatever comes to be is always complex. There is, on the one hand, something which comes to be, and again something which becomes that—the latter in two senses, either the subject or the opposite. By the opposite I mean the unmusical, by the subject, man; and similarly I call the absence of shape or form or order the opposite, and the bronze or stone or gold the [15] subject.

-

What comes to be is the Form (morphē), e.g. Musical

-

What comes to be is always a “compound” (suntheton) involving:

-

The Subject (hupokeimenon), e.g. Socrates

-

The Opposite or Privation, e.g. Non-Musical

-

-

Hence, there are (depending on how one describes the coming to be) either two or three principles:

Physics 1.7, 190b29–191a2 (Hardie and Gaye tr.)

There is a sense, therefore, in which we must declare the principles to be two, and a sense in which they are three; a sense in which the contraries are the [30] principles—say for example the musical and the unmusical, the hot and the cold, the tuned and the untuned—and a sense in which they are not, since it is impossible for the contraries to be acted on by each other. But this difficulty also is solved by the fact that what underlies is different from the contraries; for it is itself not a [35] contrary. The principles therefore are, in a way, not more in number than the contraries, but as it were two; nor yet precisely two, since there is a difference of [191 a 1] being, but three. For to be man is different from to be unmusical, and to be unformed from to be bronze.

Physics 1.8

- Aim of the chapter

- to show that only this analysis of coming to be can solve “the difficulty of the early thinkers, as well as our own”.

A Dilemmatic Argument

Physics 1.8, 191a25–31 (Hardie and Gaye tr.)

The first of those who studied philosophy … say that none of the things that are either comes to be or passes out of existence, because what comes to be must do so either from what is or from what is not, both of which are impossible.

For what is cannot come to be [30] (because it is already), and

from what is not nothing could have come to be (because something must be underlying).

-

If x comes to be, it must come to be either

-

from what is, or

-

from what is not.

-

-

x cannot come to be from what is, since what-is already is

-

x cannot come to be from what-is-not, since something must be underlying (SC, no generation ex nihilo)

-

Therefore, it is not the case that x comes to be.

The Aristotelian Intervention

Distinguish (1) coming to be from what is not without qualification (which is impossible) from (2) coming to be from what is not-F, where F is incidental to what something comes to be from:

A doctor builds a house, not qua doctor, but qua housebuilder, and turns gray, not qua [5] doctor, but qua dark-haired. On the other hand he doctors or fails to doctor qua doctor. But we are using words most appropriately when we say that a doctor does something or undergoes something, or becomes something from being a doctor, if he does, undergoes, or becomes qua doctor. Clearly then also to come to be so-and-so from what is not means ‘qua what is not’.

- The Qua Operator

- x does φ qua F iff x does φ in x’s capacity as (an) F

Responding to the Dilemma

-

Disarming the Second Horn

Recall: that which comes to be is complex, including both subject (which survives as a constituent of that which comes to be) and privation (which is something which is not and does not survive).

Physics 1.8, 191b13–17 (Hardie and Gaye tr.)

We ourselves are in agreement with them in holding that nothing can be said without qualification to come from what is not. But nevertheless we maintain that a thing may come to be from what is not in a qualified sense, i.e. accidentally. For a [15] thing comes to be from the privation, which in its own nature is something which is not—this not surviving as a constituent of the result. Yet this causes surprise, and it is thought impossible that something should come to be in the way described from what is not.

-

Disarming the First Horn

Recall: the subject in every case comes to be F from being not-F:

Physics 1.8, 191b17–25 (Hardie and Gaye tr.)

In the same way we maintain that nothing comes to be from what is, and that what is does not come to be except accidentally. In that way, however, it does, just as animal might come to be from animal, and an animal of a certain kind from an animal of a certain kind. Thus, suppose a dog to come to be from a dog, or a horse [20] from a horse. The dog would then, it is true, come to be from animal (as well as from an animal of a certain kind) but not as animal, for that is already there. But if anything is to become an animal, not accidentally, it will not be from animal; and if what is, not from what is—nor from what is not either, for it has been explained that [25] by ‘from what is not’ we mean qua what is not.

Lingering Questions

- Details of Unqualified Coming to Be

- What is the subject of substantial generation? What is the relevant privation? Isn’t it the case that substances lacks contraries (Cat. 5)?

- A Puzzling Reference

- A. claims that the same dilemma has been solved elsewhere in terms of potentiality (dunamis) and actuality (energeia). Where, and how?

Physics 1.8, 191b27–29 (Hardie and Gaye tr.)

This then is one way of solving the difficulty. Another consists in pointing out that the same things can be spoken of in terms of potentiality and actuality. But this has been done with greater precision elsewhere.

2.3 | Substantial vs. Non-Substantial Coming to Be

Basic Notions

Kinds of Coming to Be/Passing Away

- Coming-to-be/generation

- to genēsthai, genesis

- Passing away/corruption

- phthora

Cf. GC 1.4, 319b30–320a2

-

Qualified

-

Growth/Diminution: Change of contraries (metabolē tēs enantōseōs) in the category of quantity

-

Locomotion: Change of contraries in the category of place

-

Alteration: Change in the category of “affection (pathos) and quality”

-

-

Unqualified

-

Generation/Destruction: Change in which “nothing persists of which the other is generally an affection or accident”.

-

Question: Is this account of unqualified coming to be consistent with the Physics 1 account? Recall:

-

Subject Condition (SC): In every case of coming to be, there must be some underlying subject, s, such that it is true ‘s comes to be…’.

-

Persistance Condition (PC): In every case of coming to be, the underlying subject must remain one in number, although not one in form or logos.

-

-

Basics of Aristotelian Mereology

- Elements

- That into which all bodies are ultimately divided, but which are not themselves divided into anything different in kind (Metaph. 1014a32–35)

- Homoiomeres

- Lit. “same-parts”; compound bodies of which the parts are the same in kind as the whole (e.g. flesh, bone, sinew, blood)

- Functional Parts (organa)

- Compound bodies defined in terms of their function, and whose parts are not the same in kind as the whole (e.g., nose, hand)

- Substances

- Compound bodies not present in anything else as part.

Transformation of the Elements

- Sublunary Aristotelian Simple Bodies (≈ Elements)

- Earth, Air, Fire, Water

- Primary Differentia of Simple Bodies

- Hot and Cold, Wet and Dry

-

Fire: Hot + Dry

-

Air: Hot + Moist

-

Water: Cold + Moist

-

Earth: Cold + Dry

-

- Reciprocal Transformation of the Elements

- The coming to be of the elemental bodies is cyclical, effected by a replacement of a single pair of contraries between one element and the other.

-

Air comes to be from Fire by the replacement of Dry with Moist

-

Water comes to be from Air by the replacement of Cold with Hot

-

Earth comes to be from Water by the replacement of Moist with Dry

-

Fire comes to be from Earth by the replacement of Cold with Hot

-

- Question

- Is elemental transformation possible without prime matter?

The Tasks of GC 1.1–4

GC 1.1, 314a1–5 (Williams tr.)

Our task now is:

- to pick out the causes and definitions of generation and corruption common to all those things which come to be and perish in the course of nature; and

- secondly to investigate growth and alteration, asking what each of them is, and whether we are to suppose that the nature of alteration and generation is the same or different, as they are certainly distinguished in name.

-

GC 1.1–3 are concerned principally with Task 1, specifically with articulating a basic account of unqualified generation and corruption

-

GC 1.4–5 are concerned principally with Task 2, distinguishing unqualified generation from both alteration and growth

-

Why is Task 2 so pressing?

-

As A. tells us at the end of GC 1.2:

GC 1.2 317a17–26 (Williams tr.)

Nevertheless, coming to be simpliciter, i.e. absolutely, is not defined by aggregation and segregation, as some say; nor is change in what is continuous the same as alteration. This is just where all the mistakes are made. Coming to be and ceasing to be simpliciter occur, not in virtue of aggregation and segregation, but when something changes from this to that as a whole. These people think that all such change is alteration, but there is in fact a distinction. For within the substratum there is something which corresponds to the definition and something which corresponds to the matter. When, therefore, the change takes place in these it will be generation or corruption: when it takes place in the affections, accidentally, it will be alteration.

The Basic Model of Generation in GC 1.1–3

Answers 2 questions:

- What is generation/corruption without qualification (or absolutely, or simpliciter)? Why is it that some coming to be is absolute, while some is not?

GC 1.3, 317b12–34 (Williams tr.)

The dilemmas that arise concerning these matters and their solutions have been set out at greater length elsewhere, but it should now again be said by way of summary that in one way it is from what is not that a thing comes to be simpliciter, though in another way it is always from what is; for that which is potentially but is not actually must pre-exist, being described in both these ways.

But even when these distinctions have been made, there remains a question of remarkable difficulty, which we must take up once again, namely, how is coming to be simpliciter possible, whether from what is potentially or some other way. One might well wonder whether there is coming to be of substance and the individual, as opposed to quality, quantity, and place (and the same question arises in the case of ceasing to be). For if something comes to be, clearly there will exist potentially, not actually, some substance from which the coming to be will arise and into which that which ceases to be has to change. Now will any of the others belong to this actually?

What I mean is: Will that which is only potentially individual and existent, but neither individual nor existent simpliciter, have any quality or quanity or place?

If it has none of these, but all of them potentially, (a) that which in this sense is not will consequently be separable, and further, (b) the principal and perpetual fear of the early philosophers will be realized, namely, the coming to be of something from nothing previously existing.

But if being individual and a substance are not going to belong to it while some of the other things we have mentioned are, the affections will, as we have remarked, be separable from the substances.

- If there is unqualified generation/corruption, why does it persist? Why doesn’t the total quantity of bodies continually shrink into non-existence?

GC 1.3, 318b33–319a3 (Williams tr.)

We have now stated the reason why there is such a thing as generation simpliciter, which is the corruption of something, and such a thing as corruption simpliciter, which is the generation of something: it is due to a difference of matter:

- either in respect of its being substance or not being substance,

- or in respect of its being more or less so,

- or because in the one case the matter from which or to which the change takes place is more perceptible and in the other case less perceptible.

- Question

- How does this account of absolute generation apply to the transformation of the elements?

Distinguishing Absolute Generation from Alteration (GC 1.4)

GC 1.4, 319b8–21 (Williams tr.)

The substratum is one thing and the affection whose nature is to be predicated of the substratum another, and either of them can change.

- Alteration

- So it is alteration when the substratum remains, being something perceptible [i.e., a tode ti or individual] but change occurs in the affections which belong to it, whether these are contraries or intermediates. For example, the body is well then ill, but remains the same body; the bronze is now round, now a thing with corners, but remains the same [sc. bronze].

- Generation

- When, however, the whole changes without anything perceptible remaining as the same substratum, but the way:

- the seed changes entirely into blood,

- water into air,

- or air entirely into water,

then, when we have this sort of thing, it is a case of generation (and corrpution of something else); particularly if the change takes place from what is imperceptible to what is perceptible either by touch or by the other senses, as when water is generated or corrupts into air, since air is—near enough—imperceptible.

In these cases [sc. of generation] if some affection that is one of a pair of contraries remains the same in the thing generated as it was in the thing that has perished, e.g. when water comes from air, if both are transparent or <wet, but not> cold, this must not have the other, the terminus of the change, as an affection of itself. Otherwise it will be alteration.

The Unqualified Nature of Elemental Transformations

GC 1.4, 319b21–31 (RFH rough tr.)

Ἐν δὲ τούτοις ἄν τι ὑπομένῃ πάθος τὸ αὐτὸ ἐναντιώ σεως ἐν τῷ γενομένῳ καὶ τῷ φθαρέντι, οἷον ὅταν ἐξ ἀέρος ὕδωρ, εἰ ἄμφω διαφανῆ ἢ ψυχρά, οὐ δεῖ τούτου θάτερον πάθος εἶναι εἰς ὃ μεταβάλλει. Εἰ δὲ μή, ἔσται ἀλλοίωσις, [25] οἷον ὁ μουσικὸς ἄνθρωπος ἐφθάρη, ἄνθρωπος δ' ἄμουσος ἐγέ- νετο, ὁ δ' ἄνθρωπος ὑπομένει τὸ αὐτό.

Εἰ μὲν οὖν τούτου μὴ πάθος ἦν καθ' αὑτὸ ἡ μουσικὴ καὶ ἡ ἀμουσία, τοῦ μὲν γένε- σις ἦν ἄν, τοῦ δὲ φθορά· διὸ ἀνθρώπου μὲν ταῦτα πάθη, ἀνθρώπου δὲ μουσικοῦ καὶ ἀνθρώπου ἀμούσου γένεσις καὶ [30] φθορά· νῦν δὲ πάθος τοῦτο τοῦ ὑπομένοντος. Διὸ ἀλλοίωσις τὰ τοιαῦτα.

[I] In those things in which some affection from among a pair of contraries remains the same in both what comes to be and what is destroyed—for instance, when water [comes to be] from air, assuming both are transparent or

cold[moist?]—the other, into which it changes, must not be an affection of it. If it is, it will be [a case of] alteration, as [when] the musical person perishes and the unmusical person comes to be, the person remains the same.[II] Hence if musical and unmusical were not per se affections of this [sc. the person], we would have generation of the latter and passing away of the former. This is why they are affections of a person, whereas of musical person and unmusical person we have generation and destruction. As it is, however, this is an affection of what remains, for which reason [transformations] of this sort are [cases of] alteration.

- Upshot of [I]

- On pain of being cases of alteration, it cannot be supposed that the persisting subject of elemental transformations is the quality that inheres in both what comes to be and what perishes.

- Upshot of [II]

- Despite the superficial similarity in the locutions (1) “the musical person comes to be the unmusical person” and (2) “the hot moist comes to be the cold moist”, they describe two ontologically distinct changes:

-

In (1), the affections musical and unmusical are affections of the person as such, which therefore persists through the alteration as subject.

-

In (2), however, the affections hot and cold are affections of the moist only incidentally, in the way the pale thing (the person who happens to be pale) is musical or unmusical. Hence it is wrong to suppose that the moist is a subject of predication, much less that it persists through the transition from hot to cold.

-

Two Interpretive Strategies (Pros and Cons)

- Question

- What, if anything, is the subject of which moist, hot, and cold are predicated?

-

First air, then water: Coheres with A.’s denial of a persistent subject in unqualified generation, but at the cost of treating elemental transformation (and all substantial coming-to-be) as a process of “sheer replacement”.

-

Prime matter: Avoids the “sheer replacement” model, and perhaps enjoys some textual support, but the metaphysical victory is pyrrhic: what sort of improvement is it to say that water comes to be from pure potentiality?

-