Unit 5 | Applications: the Soul in Animal Generation

5.1 | Soul as the Form of a Living Body

- Recall

- Aristotle’s answer to the central ontological question, “what is substance?” or “what is the substance of x?”, is that substance is a cause of being, understood here as form in its role as efficient and/or final cause of x.

- Question

- How does this this conception of substance as both form and cause of being influence Aristotle’s approach to natural science, in particular, his zoology or science of animal life?

Big Picture: Aristotle’s Zoological Works

| Work | Contents |

|---|---|

| Historia Animalium | Organized presentation of facts (“thats”) about animal kinds |

| De Anima | Account of “nature and essence” of soul. |

| Parva Naturalia | Shorter works on attributes “common to soul and body”, incl.: |

| De Sensu: Sensation and sensible objects | |

| De Memoria: Memory and recollection | |

| De Somno: Sleep | |

| De Insomniis: Dreams | |

| De Div.: Divination in sleep | |

| De Longitudine Vitae: On the length and shortness of life | |

| De Juventute: On youth and old age | |

| De Partibus Animalium | Explains soul as final cause of animal body |

| De Generatione Animalium | Explains soul as efficient cause of animal body |

| De Incessu Animalium | Account of types of animal motion |

| De Motu Animalium | Account of psychological causes of animal motion |

The Project of De Anima

- Aim

- To determine the essence and attributes of soul.

DA 1.1, 402a1–8 (Shields tr.)

We count cognition among the fine and honourable things, and suppose that one kind of cognition is finer and more honourable than another owing to its precision or because of its having better and more marvellous objects; and for both these reasons we may reasonably place an inquiry into the soul into the premier class of study. It also seems that research into the soul contributes greatly to truth in general, and most especially to truth about nature. For the soul is a sort of first principle of animals. We aim to consider and ascertain its nature and essence, and then its properties, of which some seem to be affections peculiar to the soul itself, while others belong to animals as well because of the soul.

- Method

- By studying both the form and matter of living things, as a natural scientist would!

DA 1.1, 402b16–29 (Shields tr.)

And it would seem that all the affections of the soul involve the body—anger, gentleness, fear, pity, courage, as well as joy, and loving and hating. For at the same time as these, the body is affected in some way. This is shown by the fact that sometimes, even though strong and evident affections are present, we are not provoked or made afraid, while at other times we are moved by something small and obscure, whenever the body is agitated and in the condition it is in when angry. This is even clearer from the fact that sometimes though nothing frightful is present, people come to have the affections of a frightened person.

If this is so, it is clear that the affections are accounts in matter. Consequently, definitions will be of this sort, for example: ‘being angry is (1) a sort of motion (2) of a body of such a sort, or of a part or capacity of a body, (3) brought about by this (4) for the sake of that.’ And for these reasons, a consideration of the soul, either all souls or this sort of soul, is already in the province of the natural scientist.

Aristotle’s Definition of Soul in De Anima 2

Aristotle’s postive account of soul begins in Book 2 of De Anima, which begins somewhat predictably but marks a radical change in the focus of psychological investigation. In summary:

- De Anima 2.1

- Soul is the form and first actuality of an organic body, a body having the potential for life.

- De Anima 2.2

- This can serve only as an “outline” account of soul, since “living is said in many ways”.

- De Anima 2.3

- To formulate a “scientific” definition of soul—one that explains how soul operates as the cause of life—we must turn our attention to the principal capacities of soul, including nutrition, reproduction, perception, locomotion, and thought.

The Outline Account of Soul in De Anima 2.1

DA 2.1, 412a 5–22 (Shields tr.)

We say that among the things that exist one kind is substance, and that one sort is substance as matter, which is not in its own right some this; another is shape and form, in accordance with which it is already called some this; and the third is what comes from these. Matter is potentiality, while form is actuality; and actuality is spoken of in two ways, first as knowledge is, and second as contemplating is.

Bodies seem most of all to be substances, and among these, natural bodies, since these are the principles of the others. Among natural bodies, some have life and some do not have it. By ‘life’ we mean that which has through itself nourishment, growth, and decay.

It would follow that every natural body having life is a substance, and a substance as a compound. But since it is also a body of this sort-for it has life-the soul could not be a body; for the body is not among those things said of a subject, but rather is spoken of as a subject and as matter. It is necessary, then, that the soul is a substance as the form of a natural body which has life in potentiality. But substance is actuality; hence, the soul will be an actuality of a body of such a sort.

Two refinements:

- Soul is the actuality in the way knowledge is (= first actuality) rather than the way contemplating is (= second actuality):

DA 2.1, 412a23–29 (Shields tr.)

Actuality is spoken of in two ways, first as knowledge is, and second as contemplating is. Evidently, then, the soul is actuality as knowledge is. For both sleeping and waking depend upon the soul’s being present; and as waking is analogous to contemplating, sleeping is analogous to having knowledge without exercising it. And in the same individual knowledge is prior in generation. Hence, the soul is the first actuality of a natural body which has life in potentiality.

- A body having the potential for life is an organic (functionally organized) body:

DA 2.1, 412b1–6 (Shields tr.)

This sort of body would be one which is organic. And even the parts of plants are organs, although altogether simple ones. For example, the leaf is a shelter of the outer covering, and the outer covering of the fruit; and the roots are analogous to the mouth, since both draw in nourishment. Hence, if it is necessary to say something which is common to every soul, it would be that the soul is the first actuality of an organic natural body.

-

A Complication: the “Ackrill Problem”

-

To be the material cause of a process of generation, the body must be capable of receiving contrary forms.

-

According to DA 2.1, however, the body seems to be necessarily enformed with soul; a dead body, or a body (or body part) lacking soul is a body only homonymously:

DA 2.1, 412b25–27 (Shields tr.)

The body which has cast off its soul is not a being which is potentially such as to be alive; this is rather the one that has soul. The seed, however, and the fruit, is such a body (= a body potentially such as to be alive?) in potentiality.

-

How, then, can the body be the matter for soul?

-

The Homonymy of Life in De Anima 2.2

The account of soul offered in DA 2.1 is however only an “outline” or “general” account of soul, not a scientific definition specifying its essence. Why?

De Anima 2.2, 413a11–20 (Shields tr.)

Because what is sure and better known as conforming to reason comes to be from what is unsure but more apparent, one must try to proceed anew in this way concerning the soul. For it is not only necessary that a defining account make clear the that, which is what most definitions state, but it must also contain and make manifest the cause. As things are, statements of definitions are like conclusions. For example: ‘what is squaring? It is an equilateral rectangle being equal to an oblong figure.’ But this sort of definition is an account of the conclusion: the one who states that squaring is the discovery of a mean states the cause of the matter.

To see what Aristotle has in mind here, we need to appreciate a difficulty for the science of soul that Aristotle raised back in DA 1.1:

DA 1.1, 402b5–8 (Shields tr.)

And one must take care not to overlook the question of whether

- there is one account of soul, as there is one account of animal,

or whether

- there is a different account for each type of soul, for example, of horse, of dog, of man, of god, while the universal animal is either nothing or is posterior to these;

and it would be the same if any other common thing were being predicated.

In DA 2.2, Aristotle offers reason for thinking that “there is a different account of each type of soul”, namely that living is said in many ways:

DA 2.2, 413a21–25 (Shields tr.)

We say, then, taking up the beginning of the inquiry, that what is ensouled is distinguished from what is not ensouled by living. But living is spoken of in several ways. And should even one of these belong to something, we say that it is alive: reason, perception, motion and rest with respect to place, and further the motion in relation to nourishment, decay, and growth.

Specifically:

- Nutrition (Growth, Decay, Reproduction)

- Belongs to everything that is said to live, including plants and animals.

- Perception

- Belongs to animals but not to plants.

- Locomotion

- Belongs to some animals.

- Reason

- Belongs to apparently one kind of animal: humans.

On the assumption that soul is the cause of life in living things: how can there be a single account of soul, given how many different ways living is spoken of?

The Unity of Psychology: De Anima 2.3

Aristotle showed in DA 2.2 that no univocal definition (of the sort given in DA 2.1) of soul could capture its role as the cause of life in the many ways in which living things are said to live. Instead, we need to study the soul of each kind of living thing individually:

DA 2.3, 414b25–28 (Shields tr.)

For this reason, it is ludicrous to seek a common account in these cases, or in other cases, an account which is not peculiar to anything which exists, and which does not correspond to any proper and indivisible species, while neglecting what is of this sort. Consequently, one must ask individually what the soul of each is, for example, what the soul of a plant is, and what the soul of a man or a beast is.

This does not mean, however, that there is not unified science of psychology, as opposed to a set of unrelated sciences of botany, zoology, and anthropology. To the contrary, there is a systematic relation among the capacities of soul present in plants, animals, and humans:

DA 2.3, 414b29–415a13 (Shields tr.)

What holds in the case of the soul is very close to what holds concerning figures: for in the case of both figures and ensouled things, what is prior is always present potentially in what follows in a series—for example, the triangle in the square, and the nutritive faculty in the perceptual faculty. One must investigate the reason why they are thus in a series.

For the percepual faculty is not without the nutritive, though the nutritive faculty is separated from the perceptual in plants.

Again, without touch, none of the other senses are present, though touch is present without the others; for many animals have neither sight nor hearing nor a sense of smell.

Also, among things capable of perceiving, some have motion in respect of place, while others do not.

Lastly, and most rarely, some have reasoning and understanding. For among perishable things, to those to which reasoning belongs all the remaining capacities also belong, though it is not the case that reasoning belongs to each of those with each of the others. Rather, imagination does not belong to some, while others live by this alone.

A different account will deal with theoretical reason.

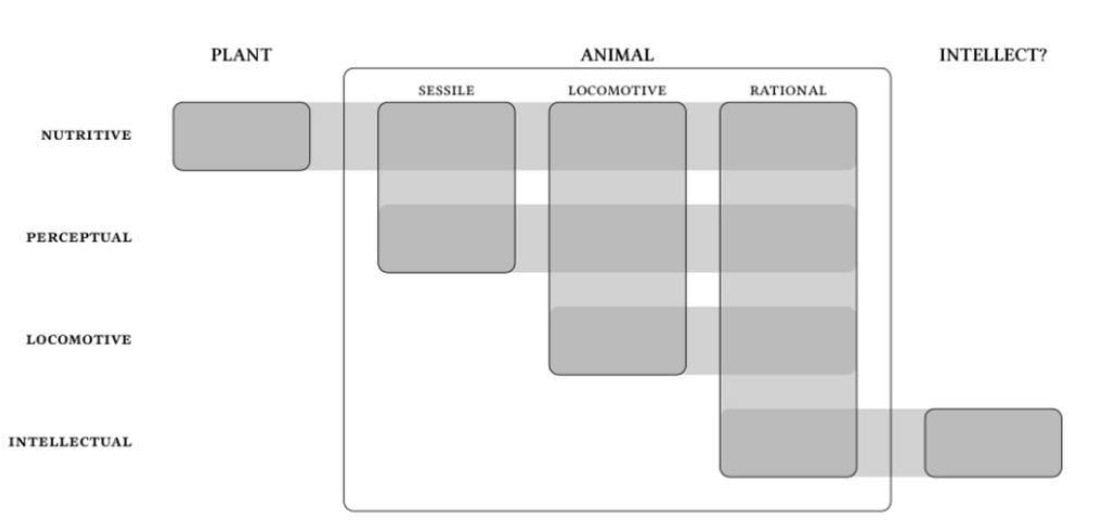

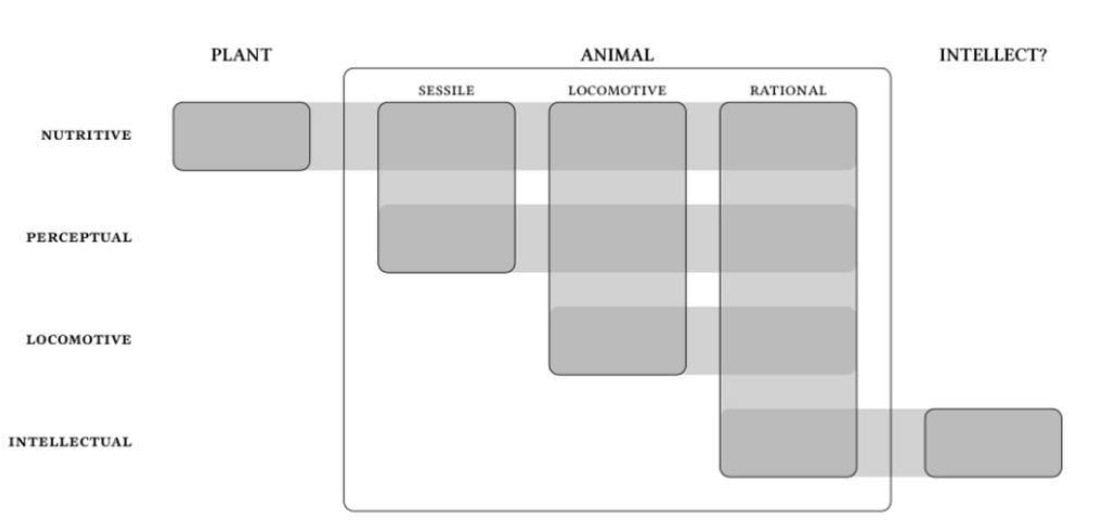

Represented schematically:

- The upshot?

- “The account of each of these [sc. capacities of soul] will also be the most appropriate account of the soul [itself]” (415a14–15).

5.2 | Closer to a Scientific Account of Soul

Our discussion of De Anima 2 left off with Aristotle on his way to a significant conclusion: the proper subject of the science of soul is not the soul itself but its constituent capacities — including the capcities for nutrition, reproduction, locomotion, and thought.

How does he arrive at this conclusion?

The Unity of Psychology

Aristotle showed in DA 2.2 that no univocal definition (of the sort given in DA 2.1) of soul could capture its role as the cause of life in the many ways in which living things are said to live. Instead, we need to study the soul of each kind of living thing individually:

DA 2.3, 414b25–28 (Shields tr.)

For this reason, it is ludicrous to seek a common account in these cases, or in other cases, an account which is not peculiar to anything which exists, and which does not correspond to any proper and indivisible species, while neglecting what is of this sort. Consequently, one must ask individually what the soul of each is, for example, what the soul of a plant is, and what the soul of a man or a beast is.

This does not mean, however, that there is not unified science of psychology, as opposed to a set of unrelated sciences of botany, zoology, and anthropology. To the contrary, there is a systematic relation among the capacities of soul present in plants, animals, and humans:

DA 2.3, 414b29–415a13 (Shields tr.)

What holds in the case of the soul is very close to what holds concerning figures: for in the case of both figures and ensouled things, what is prior is always present potentially in what follows in a series—for example, the triangle in the square, and the nutritive faculty in the perceptual faculty. One must investigate the reason why they are thus in a series.

For the percepual faculty is not without the nutritive, though the nutritive faculty is separated from the perceptual in plants.

Again, without touch, none of the other senses are present, though touch is present without the others; for many animals have neither sight nor hearing nor a sense of smell.

Also, among things capable of perceiving, some have motion in respect of place, while others do not.

Lastly, and most rarely, some have reasoning and understanding. For among perishable things, to those to which reasoning belongs all the remaining capacities also belong, though it is not the case that reasoning belongs to each of those with each of the others. Rather, imagination does not belong to some, while others live by this alone.

A different account will deal with theoretical reason.

Represented schematically:

- Therefore

- “The account of each of these [sc. capacities of soul] will also be the most appropriate account of the soul [itself]” (415a14–15).

Consequences of this Conclusion

Aristotle has defended the unity of psychology—i.e., the idea that there is a science of soul, understood as a cause of living, over and above the sciences of (e.g.) human life (anthropology), animal life (zoology), and plant life (botany)—by arguing that:

-

Psychological capcities can be shared by psychological kinds; and that

-

Psychological capacities exhibit regular patterns of ontological dependence across psychological kinds.

Two important consequences follow from this conclusion.

The Soul Operates as Cause of Life Activities in Various Ways

De Anima 2.4, 415b8–28 (Shields tr.)

The soul is the cause and principle of the living body. As these things are spoken of in many ways, so the soul is spoken of as a cause in the three of the ways delineated: for the soul is a cause (1) as the source of motion, (2) as that for the sake of which, and (3) as the substance of ensouled bodies.

That it is a cause as substance is clear: for substance is the cause of being for all things, and living is being for living things, while the cause and principle of living is the soul. Further, actuality is the logos of that which is potentially.

It is evident that the soul is a cause as that for the sake of which: just as reason acts for the sake of something, in the same way nature does so as well; and this is its end. And in living beings the soul is naturally such a thing. For all ensouled bodies are organs of the soul—just as it is for the bodies of animals, so is it for the bodies of plants—since they are for the sake of the soul. ‘That for the sake of which’ is spoken of in two ways: that on account of which and that for which.

Moreover, the soul is also that from which motion in respect of place first arises, though this capacity does not belong to all living things. There are also alteration and growth in virtue of the soul; for perception seems to be a sort of alteration, and nothing perceives which does not partake of the soul. The same holds for both growth and decay; for nothing which is not nourished decays or grows naturally, and nothing is nourished which does not have a share of life.

This consequence brings into clear focus exactly why a generic account of soul would fail to disclose the way in which soul causes living things to live: namely because, depending on the kind of life (or life activity) in question, soul operates as cause in different ways.

The Dependencies Among Psychological Capacities Stand in Need of Explanation

This is a consequence Aristotle acknowledges several times in De Anima 2:

DA 2.2 413b4–10 (Shields tr.)

Being alive, then, belongs to living things because of this principle, but something is an animal primarily because of perception. For even those things which do not move or change place, but which have perception, we call animals and not merely alive. The primary form of perception which belongs to all animals is touch. But just as the nutritive capacity can be separated from touch and from the whole of perception, so touch can be separated from the other senses. By nutritive we mean the sort of part of the soul of which even plants have a share. But all animals evidently have the sense of touch. The reason why both of these turn out to be the case we shall state later.

DA 2.2, 413b27–414a4 (Shields tr.)

It is evident from these things, though, that the remaining parts of the soul are not separable, as some assert. That they differ in account, however, is evident; for what it is to be the perceptual faculty is different from what it is to be the faculty of belief, if indeed perceiving differs from believing, and so on for each of the other faculties mentioned. Further, all of these belong to some animals, and som of them to others, and only one to still others. And this will provide a differentiation among animals. It is necessary to investigate the reason why later. Almost the same thing holds for the senses: for some animals have them all, others have some of them, and others have one, the most necessary, touch.

DA 2.3, 414b33–415a1 (Shields tr.)

One must investigate the reason why they are thus in a series.

Explaining the Serial Dependencies Among Psychological Capacities

Commentators usually look for the promised explanation in DA 3.12–13, where, among other things, Aristotle accounts for the presence of capacities in different psychological kinds by appeal to hypothetical necessity:

-

The nutritive soul is necessary for all living things to grow and reach (reproductive) maturity.

-

Perception is not necessary for plants, but for animals it is, since without the capacity to perceive:

-

Animals could not acquire food,

-

Nor could they achieve “the goal (telos) that is the function (ergon) of their nature”,

-

Nor could rational animals acquire “a discriminating mind” (nous kritikos).

-

-

Not all of the senses are necessary for every kind of animal, since only animals who need locomotion in order to find food and avoid danger require the distance senses.

-

For these “roaming” animals, moreover, these distance senses are present not only for the sake of being (to einai) and survival (sotēria), but also for the sake of well-being (to eu).

- Question

- How does this answer the question of (e.g.) why all perceivers are also self-nourishers?

A Clue to Aristotle’s Strategy

De Anima 2.4, 415a23–b7 (RFH tr.)

For the nutritive soul belongs also to the others, and is the primary and most common capacity of soul in respect of which living belongs to all. (Its functions are reproducing and [in general] using food.) For the most natural function for living things – those that are complete and not maimed or have spontaneous generation – is for it to produce another like itself, an animal an animal, a plant a plant, so that they may share as much as possible in the eternal and divine. For all strive for that, and do whatever they do by nature for the sake of that. (And that for the sake of which is double: on the one hand that of which, on the other that for which.) So, since it cannot share in the eternal and divine in continuity, on account of the inability of any perishable thing to persist one and the same in number, each shares in it as much as it can partake, some more, some less; and not it but something like it persists, not one in number, but one in species.

- Question

- What makes it true to say that all living things do everything they do by nature for the sake of sharing as much as possible in the eternal and divine?

- Possible Answer

- The end for whose sake living things are endowed with the psychological capacities they naturally have is the activity that represents the best available means for that living thing to participate in the eternal and divine:

-

For sterile or spontaneously generated animals (non-reproducers), that activity is nutrition and self-preservation.

-

For the vast majority of fertile living things, that activity is reproduction, or eternal persistence in kind.

-

For rational living things, that activity is theoretical contemplation (see EN 10.6–8).

-

5.3 | Matter & Form in Natural Reproduction

- The Project of Generation of Animals

- To consider the moving causes of animals, in particular the generation of each animal and the parts that contribute to animal generation. (GA 1.1)

Aristotle’s Place in the History of Genetics and Embryology

Two controversies in the history of embryology:

- Preformationism vs. Developmentalism

- Do all the parts of the animal exist is a preformed state (e.g. as a “homonculus”) prior to conception and/or birth, or does they develop during gestation?

How does generative seed reproduce manage to generate all the parts of the animal? Some options: - Panspermia (Hippocratic Treatises, Darwin): Each part of the body contirbutes to the production of seed.

- **Information Theory (Modern Genetics):** Seed encodes _information_ about the plan of the entire body, a plan according to which gestation unfolds.

Aristotle has the honor of being on the right side of both of these debates—a fact which led the Nobel laureate molecular biologist Max Delbrück to propose that Aristotle too be awarded the same prize for “the discovery of the principle implied in DNA”:

Delbrück 1971, 54–55

Put into modern language, what all these quotations [summarizing Aristotle’s position on these debates] is this: The form principle is the information which is stored in the semen. After fertilization it is read out in a preprogrammed way; the readout alters the matter upon which it acts, but it does not alter the stored information, which is not properly speaking, part of the finished product. In other words, if that committee in Stockholm, which has the unenviable task each year of pointing out the most creative scientists, had the liberty of giving awards posthumously, I think they should consider Aristotle for the discovery of the principle implied in DNA.

The Principles of Aristotle’s Embryology

As Delbrück alludes to, Aristotle’s account of animal generation relies fundamentally on his hylomorphism, and particularly on the idea that the principles of generation, the male and the female, correspond respectively to form and matter, the active and passive principles of the process which brings about a new organism.

Agency and Patiency in General

In this theory, Aristotle is relying on a general account of motion and change defended in Physics 3.1–3, according to which:

- Motion (kinêsis) is the fullfillment of what is potenially, qua potentially:

Physics 3.1, 201a10ff. (Hardie and Gaye tr.)

Thus the fulfilment of what is potentially, as such, is motion—e.g. the fulfilment of what is alterable, as alterable, is alteration; of what is increasable and its opposite, decreasable (there is no common name for both), increase and decrease; of what can come to be and pass away, coming to be and passing away; of what can be carried along, locomotion.

-

The source of motion (the agent or mover) always moves the patient (or that which is moved) by being actually such as the moved is in potentiality.

Physics 3.2, 202a6ff. (Hardie and Gaye tr.)

Hence motion is the fulfilment of the movable as movable, the cause being contact with what can move, so that the mover is also acted on. The mover will always transmit a form, [10] either a ‘this’ or such or so much, which, when it moves, will be the principle and cause of the motion, e.g. the actual man begets man from what is potentially man.

-

Every motion, then, is the actuality of both a mover (qua agent or mover) and a moved (qua patient or moved). This, however, gives rise to a puzzle: how can the same motion be the actuality of both moved and mover? Aristotle’s answer is that the actuality of the agent and patient are logically distinct aspects of a single motion located in the mover:

Physics 3.3, 202a14ff. (Hardie and Gaye tr.)

The solution of the difficulty is plain: motion is in the movable. It is the fulfilment of this potentiality by the action of that which has the power of causing [15] motion; and the actuality of that which has the power of causing motion is not other than the actuality of the movable; for it must be the fulfilment of both. A thing is capable of causing motion because it can do this, it is a mover because it actually does it. But it is on the movable that it is capable of acting. Hence there is a single actuality of both alike, just as one to two and two to one are the same interval, and the steep ascent and the steep descent are one—for these are one and the same, [20] although their definitions are not one. So it is with the mover and the moved.

A Puzzle for Animal Generation

This solution is central to resolving an initial puzzle for animal generation, namely:

GA 1.21, 729b1 ff. (Platt tr.)

… how it is that the male contributes to generation and how it is that the semen from the male is the cause of the offspring.

Does it exist in the body of the embryo as a part of it from the first, mingling with the material which comes from [5] the female?

Or does the semen communicate nothing to the material body of the embryo but only to the power and movement in it? For this power is that which acts and makes, while that which is made and receives the form is the residue of the secretion in the female.

- Aristotle’s answer is consistent with his solution to the puzzle concerning change in general from Physics 3:

GA 1.21, 729b9 ff. (Platt tr.)

Now the latter alternative appears to be the right one both a priori and in view of the facts. For, if we consider the question on general grounds, [10] we find that, whenever one thing is made from two of which one is active and the other passive, the active agent does not exist in that which is made; and, still more generally, the same applies when one thing moves and another is moved. But the female, as female, is passive, and the male, as male, is active, and the principle of the movement comes from him. Therefore, if we take the highest genera under [15] which they each fall, the one being active and motive and the other passive and moved, that one thing which is produced comes from them only in the sense in which a bed comes into being from the carpenter and the wood, or in which a ball comes into being from the wax and the form. It is plain then that it is not necessary that anything at all should come away from the male, and if anything does come away it does not follow that this gives rise to the embryo as being in the embryo, but only as that which imparts the motion and as the form; so the medical art cures the [20] patient.

- In general, the male principle acts as mover in the process of generation in the way the art of carpentry shapes the wood that comes to be a bed, namely, by imparting a series of motions (embodied in the tools of the carpenter’s trade) that act intermediately on the wood:

GA 1.22, 730b9 ff. (Platt tr.)

From these considerations we may also gather how it is that the male [10] contributes to generation. The male does not emit semen at all in some animals, and where he does this is no part of the resulting embryo; just so no material part comes from the carpenter to the material, i.e. the wood in which he works, nor does any part of the carpenter’s art exist within what he makes, but the shape and the form [15] are imparted from him to the material by means of the motion he sets up. It is his hands that move his tools, his tools that move the material; it is his knowledge of his art, and his soul, in which is the form, that move his hands or any other part of him with a motion of some definite kind, a motion varying with the varying nature of the [20] object made. In like manner, in the male of those animals which emit semen, nature uses the semen as a tool and as possessing motion in actuality, just as tools are used in the products of any art, for in them lies in a certain sense the motion of the art. Such, then, is the way in which these males contribute to generation. But when the [25] male does not emit semen, but the female inserts some part of herself into the male, this is parallel to a case in which a man should carry the material to the workman. For by reason of weakness in such males nature is not able to do anything by any secondary means, but the movements imparted to the material are scarcely strong enough when nature itself watches over them. Thus here nature resembles a [30] modeller in clay rather than a carpenter, for she does not touch the work she is forming by means of tools, but with her own hands.

Explaining Sexual Dimorphism in Animals

For Aristotle, the principles of animal generation are also the principles of plant generation, the only difference being that the male and female principles are separate from one another in animals (although the unite, plantlike, in copulation).

Aristotle attributes the sexual differentiation of animals to the wisdom of animal nature:

GA 1.23, 731a24 ff. (Platt tr.)

For to the essence of plants [25] belongs no other function or business than the production of seed; since, then, this is brought about by the union of male and female, nature has mixed these and set them together in plants, so that the sexes are not divided in them. Plants, however, have been investigated elsewhere. But the function of the animal is not only to [30] generate (which is common to all living things), but they all of them participate also in a kind of knowledge, some more and some less, and some very little indeed. For they have sense-perception, and this is a kind of knowledge. (If we consider the value of this we find that it is of great importance compared with the class of lifeless objects, but of little compared with the use of the intellect. For against the latter the [731b1] mere participation in touch and taste seems to be practically nothing, but beside plants and stones it seems most excellent; for it would seem a treasure to gain even this kind of knowledge rather than to lie in a state of death and non-existence.) Now it is by sense-perception that an animal differs from those organisms which have only life. But since, if it is a living animal, it must also live; therefore, when it is [5] necessary for it to accomplish the function of that which has life, it unites and copulates, becoming like a plant, as we said before.

- PS

- I suspect that the underlined passage gives us a clue to what A. means when he claims in DA 2.3 that the capacities prior in the series of souls are present potentially in the latter…

- Question

- This seems however to be only part of the explanation; we need further to see why the existence of an additional cognitive function in animals accounts for their sexual dimorphism.

To the extent that Aristotle offers an answer, it comes in GA 2.1, where Aristotle claims that sexual differentiation of animal species arises both on account of necessity and for the sake of an end: - Necessity: Females are the result of the failure of the male principle to “master” the matter in embryological development; a product of material necessity. (GA 4.1)

- **Teleology:** The male and female principles are separate in animals for the sake of the greater perfection of the superior principle, which (for Aristotle) is the male:

GA 2.1, 731b24 ff. (Platt tr.)

Now some existing things are eternal and divine whilst others admit of both [25] existence and non-existence. But that which is noble and divine is always, in virtue of its own nature, the cause of the better in such things as admit of being better or worse, and what is not eternal does admit of existence and non-existence, and can partake in the better and the worse. And soul is better than body, and the living, having soul, is thereby better than the lifeless which has none, and being is better [30] than not being, living than not living. These, then, are the reasons of the generation of animals. For since it is impossible that such a class of things as animals should be of an eternal nature, therefore that which comes into being is eternal in the only way possible. Now it is impossible for it to be eternal as an individual—for the substance of the things that are is in the particular; and if it were such it would be eternal—but it is possible for it as a species.

This is why there is always a class of [732a1] men and animals and plants. But since the male and female are the first principles of these, they will exist in those things that possess them for the sake of generation.

Again, as the first efficient or moving cause, to which belong the definition and the form, is better and more divine in its nature than the material on which it works, it is [5] better that the superior principle should be separated from the inferior.

Therefore, wherever it is possible and so far as it is possible, the male is separated from the female.

For the first principle of the movement, whereby that which comes into being is male, is better and more divine, and the female is the matter.

The male, [10] however, comes together and mingles with the female for the work of generation, because this is common to both.

No comment…

5.4 | Aristotle’s Model of Embryogenesis

Introduction to Embryogenesis

In GA 2, Aristotle turns from his discussion of the principles of natural generation, the male and the female, to the question of how these principles generate offspring, a new substance the same in kind as the parents.

Recall:

- Female Principle

- The patient of natural generation; that which provides the matter for the substantial change.

- Male Principle

- The agent of natural generation; that which shapes the matter into the

By appeal to these principles, Aristotle applies the account of natural generation we saw him defend in GC 2.9, although substantial puzzles remain:

GA 2.1, 733b24 ff. (Platt tr.)

There is a considerable difficulty in understanding how the plant is formed out [25] of the seed or any animal out of the semen.

Everything that comes into being or is made must (1) be made out of something, (2) be made by the agency of something, and must (3) become something.

Now (1) that out of which it is made is the material; this some animals have in its first form within themselves, taking it from the female parent, as all those which are not born alive but produced as a grub or an egg; others receive it [30] from the mother for a long time by sucking, as the young of all those which are not only externally but also internally viviparous. Such, then, is the material out of which things come into being,

but we now are inquiring not out of what the parts of an animal are made, but (2) by what agency.

(2a) Either it is something external which makes them,

(2b) or else something existing in the seminal fluid and the semen; and this must either be

(2b') soul

(2b'') or a part of soul,

(2b''') or something containing soul.

Generation of the Offspring

The Leaving Home Analogy

The puzzle over the nature of the male principle’s agency in natural generation results from a kind of dilemma:

-

“Man begets man”, so the cause of animal generation must be what is actually such as the offspring is potentially. Therefore the agent must be the male parent.

-

Alternatively, change requires contact between agent and patent, but in many cases of animal generation the male parent is in contact with the female only indirectly, by means of the presence of the male seed in the uterus. If then, the cause of animal generation is what is actually such as what the offspring is potentially, the male seed must be actually alive, and an animal! [= 2b]

Aristotle’s solution to this puzzle is typical: we can distinguish a variety of ways in which a thing (e.g. the male seed) can be said to have soul:

GA 2.1, 735a9 ff. (Platt tr.)

But a thing existing potentially may be nearer or further from its realization in [10] actuality, just as a sleeping geometer is further away than one awake and the latter than one actually studying.

- C1

- Accordingly it is not any part that is the cause of the soul’s coming into being, but it is the first moving cause from outside. (= 2a) For nothing generates itself, though when it has come into being it thenceforward increases itself.

- C2

- Hence it is that only one part comes into being first and not all of them together.

But that must first come into being which has a principle of increase (for [15] this nutritive power exists in all alike, whether animals or plants, and this is the same as the power that enables an animal or plant to generate another like itself, that being the function of them all if naturally perfect).

And this is necessary for the reason that whenever a living thing is produced it must grow.

It is produced, then, by something else of the same name, as e.g. man is produced by man, but it is [20] increased by means of itself. There is, then, something which increases it. If this is a single part, this must come into being first. Therefore if the heart is first made in some animals, and what is analogous to the heart in the others which have no heart, it is from this or its analogue that the first principle of movement would arise.

Aristotle compares this process to that of a son who leaves his father’s home to establish one for himself:

GA 2.4, 739b34 ff. (Platt tr.)

When the embryo is once formed, it acts like the seeds of plants.

For seeds also [35] contain the first principle of growth in themselves, and when this (which previously exists in them only potentially) has been differentiated, the shoot and the root are [740a1] sent off from it, and it is by the root the plant gets nourishment; for it needs growth.

So also in the embryo all the parts exist potentially in a way, but the first principle is furthest on the road to realization.

Therefore the heart is first differentiated in [5] actuality.

- This is clear not only to the senses (for it is so) but also on theoretical grounds. For whenever the young animal has been separated from both parents it must be able to manage itself, like a son who has set up house away from his father.

Hence it must have a first principle from which comes the ordering of the body at a later stage also,

for if it is to come in from outside at a later period to dwell in it, not [10] only may the question be asked at what time it is to do so,

but also we may object that, when each of the parts is separating from the rest, it is necessary that this principle should exist first from which comes growth and movement to the other parts.

We will have a lot to say about the primacy of the heart (or its analogue in bloodless animals) in embryogenesis. First, let’s consider the prior question of how it is that the embro is formed from the interaction of the male and female.

Coming-to-Be of the Embryo

We’ve seen that Aristotle’s account of the agent of natural generation relies on the idea that that the male seed has soul potentially but not actually. In fact, this is a point Aristotle also makes about the female seed—a fact confirmed in his eyes by the phenomenon of “wind-eggs”.

GA 2.3, 735b8 ff. (Platt tr.)

It is plain that the semen and the embryo (here = female seed), while not yet separate, must be assumed to have the nutritive soul potentially, but not actually, until (like those [10] embryos that are separated from the mother) it absorbs nourishment and performs the function of the nutritive soul. For at first all such embryos seem to live the life of a plant.

And it is clear that we must be guided by this in speaking of the sensitive and the rational soul. For all three kinds of soul, not only the nutritive, must be possessed potentially before they are possessed in actuality.

And it is necessary [15] either that they should all come into being in the embryo without existing previously outside it, or that they should all exist previously, or that some should so exist and others not. Again, it is necessary that they should either come into being in the material supplied by the female without entering with the semen of the male, or come from the male and be imparted to the material in the female. If the latter, then either all of them, or none, or some must come into being in the male from [20] outside.

Aristotle attributes to the male seed the cause of the coming into being of the perceptive soul (which is what makes the embryo an animal). Puzzlingly, though, neither it nor the female seed are responsible for the coming to be of the rational soul; rather, it comes from “without” (736b27).

When the male and female principles are jointly activated, their respective potentials for soul are brought into actuality. Aristotle compares this process to the curdling of milk in the process of cheese-making.

GA 2.4, 739b20 ff. (Platt tr.)

[20] When the material secreted by the female in the uterus has been fixed by the semen of the male (this acts in the same way as rennet acts upon milk, for rennet is a kind of milk containing vital heat, which brings into one mass and fixes the similar material, and the relation of the semen to the menstrual blood in the same, milk and [25] the menstrual blood being of the same nature)—when, I say, the more solid part comes together, the liquid is separated off from it, and as the earthy parts solidify membranes form all round it; this is both a necessary result and for the sake of something, the former because the surface of a mass must solidify on heating as well as on cooling, the latter because the foetus must not be in a liquid but be separated [30] from it. Some of these are called membranes and others choria, the difference being one of more or less, and they exist in ovipara and vivipara alike.

The process however is not just one of determining a bodily distinction between the embryo and the female seed. Given Aristotle’s committment to the Homonymy Principle, no part of soul can be actually present in the embryo without the bodily organ necessary for its exercise. Hence, the “setting” or “fixing” of the embryo must coincide with the formation of the bodily organ for the capacity (or capacities?) of soul responsible for the following functions:

-

Growth

-

The “body plan”, the principle which determines the order of embryological development.

Aristotle identifies this organ as the heart, or it’s analogue in bloodless animals. Why?

The Heart and Its Role in Embryogenesis

Background: De Anima

To answer this quesiton, I think we need to recall some important conclusions of Aristotle’s discussion of nutritive soul in DA 2.4:

- 415a24–25

- The nutritive soul is the capacity for both nutrition/growth and reproduction, both of which concern the processing and use of nutriment.

Of these functions, reproduction takes teleological primacy, both over nutrition/growth but also over the other capacities of the soul: - 416b24–25: “Since it is proper to call each thing after its telos, and the telos is to generate another like oneself, the primary soul would be the faculty of generating another like oneself.

- **415a25--b7:** The teleologically primary activity of most living things---those that are not sterile or spontaneously generated---is to generate another like themselves, since this (= eternity in form) is the best available means for most living things to participate in the eternal and divine.

Moreover, as I argued in connection with DA 3.12–13, the status of reproduction as the teleologically primary activity—that activity for whose sake living things do all they do by nature—enables Aristotle to explain the presence of other psychological capacities in living things by reference to their contribution to the living thing’s ability to reach reproductive maturity and reproduce.

- Nutrition/Growth

- All living things must take in food in order to grow and reach reproductive maturity.

- Sense Perception

- Animals require senses, minimally touch and taste, in order to acquire the food they need to nourish themselves and grow.

- Distance Senses: Roaming animals additionally require distance senses in order to spot food (as well as potential threats) from afar.

This explanatory connection between reproduction and the other capacities and instrumental parts of the animal enables Aristotle to account for the order of the development of the parts of the animal in embrogenesis. In this sense, the nutritive soul contains the “body plan” of the entire organism, since the order of development and the ultimate morphology of the animal body will be the result of what it needs in order to achieve its teleologically primary activity.

Explaining the Order of Embryological Development

Aristotle’s account of the order (ti meta ti) of embryological development is designed to explain three key observations about animal development:

-

That the heart (or its analogue) develops first

-

That the internal organs develop before the external parts

-

That the upper parts of the animal develop before the lower

Unsurprisingly, Aristotle attempts to explain these facts by appeal to the teleological character of embryological development. This order, he argues can be explained on analogy with acquiring knowledge of how to play a musical instrument:

GA 2.6, 742a17 ff. (Platt tr.)

It is with the parts as with other things; one naturally exists prior to another. But the word ‘prior’ is used in more senses than one.

For there is a difference between (1) the end or final cause and (2) that which exists for the sake of it; the latter is prior in order [20] of development, the former is prior in essence.

Again, that which exists for the sake of the end admits of division into two classes, (2a) first the origin of the movement, and then (2b) that which is used by the end; I mean, for instance, that which can generate, and that which serves as an instrument to what is generated,

for the one of these, that which makes, must exist first, as the teacher before the learner, and the other [25] later, as the pipes are later than he who learns to play upon them,

for it is superfluous that men who do not know how to play should have pipes.

Thus there are three things: (1) first, the end, by which we mean that for the sake of which something else exists; (2a) secondly, the principle of movement and of generation, [30] existing for the sake of the end (for that which can make and generate, considered simply as such, exists only in relation to what is made and generated); (2b) thirdly, the useful, that is to say what the end uses.

Aristotle distinguishes three relata of teleological priority:

- End

- or that for the sake of which, e.g. the student learning to play the flute.

- Source of Motion/Generation

- which is for the sake of the End as cause of its coming to be, e.g. the teacher, who causes the student to learn the flute.

- Tools

- which are for the sake of the End as instruments (ὀργανικά) used by the End for its exercise, e.g. flutes.

The Source of Motion/Generation must be prior in generation to the End, since e.g. there can be no learner without a teacher.

But the End must be prior in generation to the Tools, since the latter are for the sake of the former: - Flutes are posterior to the learner, since “it is superfluous for one who does not know how to play the flute to have flutes” (742a27–28)

- Likewise, it would be superfluous for the end to possess tools which it could not yet use.

- _Hence_, the end must be developmentally prior to what is for the sake of it, but not as a source of motion/generation.

Aristotle uses this distinction in particular to explain the developmental priority of the part that contains the principle described above, i.e. the heart or its analogue, relative to the other parts of the body:

GA 2.6, 742a33 ff. (RFH tr.)

Given that, it is necessary for there first to be some part in which the principle of motion is present—for of course this part too is one part of the end, indeed the most controlling part). Next, after this [it is necessary for there to be] the whole and the end. Third and finally, [it is necessary for there to be] the parts instrumental for these [sc. previous parts] in relation to various uses.

Therefore if there is any such [part] that must be present in animals, [viz.] the part containing the source and end of [the animal’s] entire nature, this must be generated first: first qua productive of motion, but along with the whole qua part of the end. Therefore those among the instrumental parts that are generative of the [animal’s] nature must in every case be present first, since they are for the sake of something else as principle, whereas those which are not such among the things for the sake of something else are posterior.

Aristotle’s claim is that the part that “contains the source and end of [the animal’s] entire nature” (742b1–3) develops first qua Source of Motion (i.e. organ of nutritive soul in its threptic capacity), then qua (part of the) End (i.e. organ of nutritive soul in its reproductive capacity, perhaps as well as ultimate organ of perception; cf. 743b26–28).

Animal Nature as a Good Household Manager

This accounts for the developmental priority of the heart. What about that of the upper parts relative to the lower parts and the internal parts relative to the external parts? The same sort of explanation applies, e.g.:

GA 2.6, 742b13 ff. (Platt tr.)

And for this reason that part which contains the first principle comes into being first, next to this the upper half of the body. This is why [15] the parts about the head, and particularly the eyes, appear largest in the embryo at an early stage, while the parts below the umbilicus, as the legs, are small; for the lower parts are for the sake of the upper, and are neither parts of the end nor able to form it.

All tolled, Aristotle envisions a 4-stage process:

- Stage 1

- The heart (or its analogue) qua organ of generative principle.

- Stage 2

- The heart (or its analogue) qua organ of animal’s natural end.

- Stage 3

- “Instrumental” parts that are “parts of the end” [= organs for vital activities present for the sake of realizing the teleologically primary activity]

- Stage 4

- “Instrumental” parts that are not “parts of the end” [= organs present for the sake of vital activities]

There is, of course, a material component to these relations of developmental priority and posteriority, a component Aristotle takes to be reflected in the quality of the material (nutriment) from which each part is developed:

GA 2.6, 744b11–27 (Leunissen tr.)

Each of the other parts [i.e., instrumental parts arising in Stages 3–4 ] is formed out of the nutriment, [ Stage 3 ] the parts that are the noblest and that partake in the most important principle are formed from the nutriment which is concocted first and is purest; [ Stage 4 ] the parts that are necessary, that is to say that are for the sake of the former parts, are formed from the inferior nutriment and the residues and leftovers. For just like a good housekeeper, so also nature is not in the habit of throwing away anything from which it is possible to make anything useful. Now in a household the best part of the food that comes in is set apart for [ Stage 3 ] the free people, the inferior and the residue for [ Stage 4.1 ] the slaves, and the worst is given to [ Stage 4.2 ] the animals that live with them. Just as the intellect from the outside does those things with a view to growth, so nature in the things coming to be forms from the purest material [ Stage 3 ] the flesh and the body of the other sense organs, and from the residues thereof [ Stage 4.1 ] bones and sinews and [ Stage 4.2 ] hair, and also nails and hoofs and all similar parts; for this reason these are the last to assume their formation, for they have to wait till the time when nature has some residue to spare.

On the division of embryogenetic stages I proposed:

- Stage 3

- Organs whose functions are vital activities and part of the end of the animal’s nature (e.g. the peripheral sense organs) are formed out of first nutriment, i.e. blood.

- Stage 4

- Organs whose functions are for the sake of vital activities but not part of the end of the animal’s nature are formed out of inferior nutriment:

-

4.1: Organs whose functions are for the sake of vital activities and necessary for the animal (e.g. bones, sinews) are made from the residues of Stage 3 parts.

-

4.2: Organs whose functions are for the sake of vital activities, but which are not necessary but optimal for their performance (e.g. hair, nails, hooves) are made from whatever residue is left over.

On the view I have defended, each stage of this process occurs when and in exactly the way it does as a result of the body plan instituted by the part of living thing that contains “the end of its nature”, it’s teleologically primary activity. This view is not shared by all interpreters…

-