Unit 4 | Consequences for a Theory of Substance

4.1 | Is Substance Matter, Form, or What is From Them? Some Puzzles

Preliminaries: Aristotle’s Metaphysics

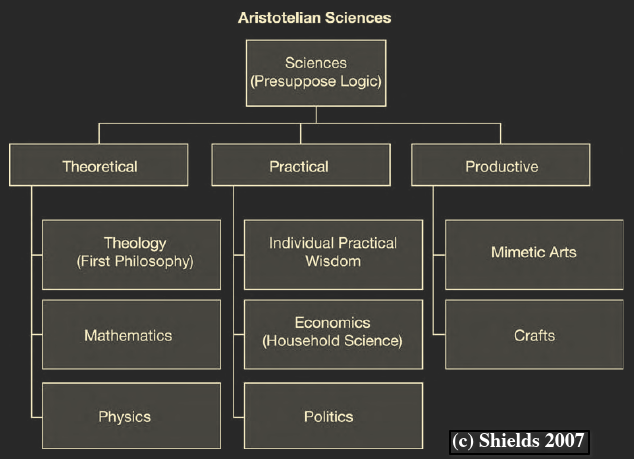

Aristotle’s Metaphysics (literally “after the Physics") is a work on “First Philosophy” or “Theology”, what, for Aristotle, amounts to the science of “being qua being”. What does this mean?

Aristotle’s Division of Sciences (Metaph. E.1)

- Theoretical Sciences

- Sciences that aim at no end beyond understanding itself.

- Physics (Natural Philosophy): Studies beings that are movable and inseparable from matter qua movable and inseparable (in thought) from matter.

- Mathematics: Studies beings that are movable and inseparable from matter qua immovable and separable (in thought) from matter.

- Theology (First Philosophy): Studies immovable, separable being qua immovable and separable.

- Question

- What makes this identical to the study of being as such?

“Being is said in many ways”

-

Aristotle is committed to the existence of a unified science of being…

Metaphysics Γ.1 (Ross tr.)

There is a science which investigates being as being and the attributes which belong to this in virtue of its own nature. Now this is not the same as any of the so-called special sciences; for none of these others deals generally with being as [25] being. They cut off a part of being and investigate the attributes of this part—this is what the mathematical sciences for instance do. Now since we are seeking the first principles and the highest causes, clearly there must be some thing to which these belong in virtue of its own nature. If then our predecessors who sought the elements of existing things were seeking these same principles, it is necessary that the [30] elements must be elements of being not by accident but just because it is being. Therefore it is of being as being that we also must grasp the first causes.

-

But there is a problem…

Being is said in many ways!

Metaphysics Z.1, 1028a9–12 (Ross tr.)

There are several senses in which a thing may be said to be, as we pointed [10] out previously in our book on the various senses of words; for in one sense it means what a thing is or a ‘this’, and in another sense it means that a thing is of a certain quality or quantity or has some such predicate asserted of it.

-

Solution?

Being has a “primary sense”, namely substance:

Metaphysics Z.1, 1028a12–19 (Ross tr.)

While ‘being’ has all these senses, obviously that which is primarily is the ‘what’, which indicates the substance of the thing. For when we say of what quality a thing is, we say that it is [15] good or beautiful, but not that it is three cubits long or that it is a man; but when we say what it is, we do not say ‘white’ or ‘hot’ or ‘three cubits long’, but ‘man’ or ‘God’. And all other things are said to be because they are, some of them, quantities of that which is in this primary sense, others qualities of it, others affections of it, and others some other determination of it.

-

Background to the Solution

Being is spoken of “pros hen”, i.e. in relation to one, primary referent:

Metaphysics Γ.2, 1003a33–b18 (Ross tr.)

There are many senses in which a thing may be said to ‘be’, but they are related to one central point, one definite kind of thing, and are not homonymous. [35]

-

Everything which is healthy is related to health, one thing in the sense that it preserves health, another in the sense that it produces it, another in the sense that it is a symptom of health, another because it is capable of it. And that which is [1003b1] medical is relative to the medical art, one thing in the sense that it possesses it, another in the sense that it is naturally adapted to it, another in the sense that it is a function of the medical art. And we shall find other words used similarly to these.

-

[5] So, too, there are many senses in which a thing is said to be, but all refer to one starting-point; some things are said to be because they are substances, others because they are affections of substance, others because they are a process towards substance, or destructions or privations or qualities of substance, or productive or generative of substance, or of things which are relative to substance, or negations of [10] some of these things or of substance itself.

[…]

As, then, there is one science which deals with all healthy things, the same applies in the other cases also. […] It is clear then that it is the work of one science [15] also to study all things that are, qua being.

But everywhere science deals chiefly with that which is primary, and on which the other things depend, and in virtue of which they get their names. If, then, this is substance, it is of substances that the philosopher must grasp the principles and the causes.

Hence the grand conclusion of Metaphysics Z.1 (1028b3–5, Ross tr.)

And indeed the question which, both now and of old, has always been raised, and always been the subject of doubt, viz. what being is, is just the question, what is [5] substance?

-

-

Aside on First Philosophy as Theology

Question : What is “being” in the primary sense?

Answer : Substance, but “there are three kinds of substance” (Metaphysics Λ.1): - Natural: i.e., movable, of which there are two kinds: - Perishable: Plants, animals, their parts, simple bodies

- **Eternal:** Celestial substances - **Immovable:** Unchanging, separable from matter.Immovable substance is the first principle of all (and, according to many commentators, being in the primary sense):

Metaphysics Λ.6, 1071b3–21

Since there were three kinds of substance, two of them natural and one unmovable, regarding the latter we must assert that it is necessary that there should be an eternal unmovable substance. For substances are the first of existing things, [5] and if they are all destructible, all things are destructible. But it is impossible that movement should either come into being or cease to be; for it must always have existed.

[…]

There must, then, be such a principle, whose very substance is [20] actuality. Further, then, these substances must be without matter; for they must be eternal, at least if anything else is eternal. Therefore they must be actuality.

The Project of Metaphysics Z

To answer the question, “what is subsance (ousia)”?

Metaphysics Z.2, 1028b27–33 (Ross tr.)

Regarding these matters, then, we must inquire which of the common statements are right and which are not right, and what things are substances, and whether there are or are not any besides sensible substances, and how sensible [30] substances exist, and whether there is a separable substance (and if so why and how) or there is no substance separable from sensible substances; and we must first sketch the nature of substance.

What is the nature of substance?

Metaphysics Z.3, 1028b34–1029a6 (Ross tr.)

The word ‘substance’ is applied, if not in more senses, still at least to four main objects; for both (1) the essence and (2) the universal and (3) the genus are thought to be [35] the substance of each thing, and fourthly (4) the substratum.

Now (4) the substratum is that of which other things are predicated, while it is itself not predicated of anything else. And so we must first determine the nature of this; for that which underlies a [1029a1] thing primarily is thought to be in the truest sense its substance. And:

in one sense (4a) matter is said to be of the nature of substratum,

in another, (4b) shape, and

in a third sense, (4c) the compound of these.

By the matter I mean, for instance, the bronze, by the shape the plan of its form, and by the compound of these (the concrete thing) the [5] statue. Therefore if the form is prior to the matter and more real, it will be prior to the compound also for the same reason.

- Observation 1

- Aristotle moves quickly from the question “what is substance” to the question “what is the substance of each thing”? (Cf. the following lines: “We have now outlined the nature of substance, showing that it is that which is not predicated of a subject, but of which all else is predicated.")

- Question: Are these questions equivalent?

- Observation 2

- Aristotle offers four candidates for an answer to the question(s) “what is substance?” and/or “what is the substance of x?":

- The essence of (“what-being-is for”) x.

- The universal to which x (qua substance?) belongs.

- The genus to which x belongs.

- The substatum of (that which underlies) x.

- Procedure of Metaphysics Z :: Aristotle will create problems for each of these candidates, only to propose (in Z.17) an entirely different account of substance grounded in the notion that substance is a cause of being.

Substance as Substratum (Z.3)

- Question

- Why cannot the substance of x be identified with that which underlies x?

- Answer

- If it were, “matter becomes substance”:

Metaphysics Z.3, 1029a9–32 (Ross tr.)

For if this is not substance, it is [10] beyond us to say what else is. When all else is taken away evidently nothing but matter remains. For of the other elements some are affections, products, and capacities of bodies, while length, breadth, and depth are quantities and not substances. For a quantity is not a substance; but the substance is rather that to [15] which these belong primarily. But when length and breadth and depth are taken away we see nothing left except that which is bounded by these, whatever it be; so that to those who consider the question thus matter alone must seem to be substance. By matter I mean that which in itself is neither a particular thing nor of a [20] certain quantity nor assigned to any other of the categories by which being is determined.

[…]

But this is impossible; for both separability and individuality are thought to belong chiefly to substance. And so form and the compound of form and matter would be thought to be substance, rather than matter. The substance compounded of both, [30] i.e. of matter and shape, may be dismissed; for it is posterior and its nature is obvious. And matter also is in a sense manifest. But we must inquire into the third kind of substance [i.e., form]; for this is the most difficult.

Substance as Essence (Z.4–6)

- Questions arising:

-

Q1: Are there essences only of substances like Socrates, or can there be an essence of red or being in Athens as well?

-

If only of substance: What defines what it is to be red?

-

If not only of substance: Then, absurdy, red would be substance, if substance is essence.

-

-

Q2: If the essence is the substance of x, and if x is identical with its substance, can x be identical with the essence of x?

-

If yes: Contradictions abound! (The “pale man” argument…)

-

If no: What would explain the difference between a thing and its essence?

-

-

Q1 (Z.4)

- Answer to Q1

- Essence belongs primarily to substance, but derivatively to items in non-substance categories…

1030a27–b13 (Ross tr.)

Now we must inquire how we should express ourselves on each point, but still more how the facts actually stand. And so now also since it is evident what language we use, essence will belong, just as the ‘what’ does, primarily and in the simple sense to substance, and in a secondary way to the other categories also,—not essence [30] simply, but the essence of a quality or of a quantity. For it must be either homonymously that we say these are, or by making qualifications and abstractions (in the way in which that which is not known may be said to be known),—the truth being that we use the word neither homonymously nor in the same sense, but just as we apply the word ‘medical’ when there is a reference to one and the same thing, not meaning one and the same thing, nor yet speaking homonymously; for a patient and [1030b1] an operation and an instrument are called medical neither homonymously nor in virtue of one thing, but with reference to one thing. But it does not matter in which of the two ways one likes to describe the facts; this is evident, that definition and essence in the primary and simple sense belong to substances. Still they belong to [5] other things as well in a similar way, but not primarily.

Q1 (Z.6)

Answer unclear…

-

The Pale Man Argument (1031a19–25)

- The pale man is the same as the essence of the pale man (“yes” to Q2)

- The man is the same as the pale man (assumption)

- So, the essence of the man is the same as the essence of the pale man.

-

A thing can’t be separate from its essence!

1031b28–1032a4 (Ross tr.)

The absurdity of the separation would appear also if one were to assign a name to each of the essences; for there would be another essence besides the original one, e.g. to the essence of horse there will belong a second essence. Yet why should not [30] some things be their essences from the start, since essence is substance? But not only are a thing and its essence one, but the formula of them is also the same, as is [1032a1] clear even from what has been said; for it is not by accident that the essence of one, and the one, are one. Further, if they were different, the process would go on to infinity; for we should have the essence of one, and the one, so that in their case also the same infinite regress would be found. Clearly, then, each primary and self-subsistent thing is one and the same as its essence.

4.2 | Solutions: Substance as a Cause of Being

Aristotle’s “Fresh Start” in Metaphysics Z.17

Metaphysics Z.17, 1041a6–22 (Ross tr.)

We should say what, and what sort of thing, substance is, taking another starting-point; for perhaps from this we shall get a clear view also of that substance which exists apart from sensible substances.

Since, then, substance is a principle and a cause, let us attack it from this standpoint.

- Observation

- The ‘why’ is always [10] sought in this form—‘why does one thing attach to another?’ For to inquire why the musical man is a musical man, is either to inquire—as we have said—why the man is musical, or it is something else.

- Objection

- Now ‘why a thing is itself’ is doubtless a meaningless inquiry; for the fact or the existence of the thing must already be [15] evident (e.g. that the moon is eclipsed), but the fact that a thing is itself is the single formula and the single cause to all such questions as why the man is man, or the musical musical, unless one were to say that each thing is inseparable from itself; and its being one just meant this.

- Revision

- This, however, is common to all things and is a short and easy way with the question. But we can inquire why man is an animal of [20] such and such a nature. Here, then, we are evidently not inquiring why he who is a man is a man. We are inquiring, then, why something is predicable of something…

Background: Inquiry and Explanation in the Analytics

How Is Inquiry Possible? Meno’s Paradox

Recall Meno’s Paradox:

- P1

- For any item of knowledge, x, either one knows x or one does not know x.

- P2

- If one knows x, one cannot inquire about x.

- P3

- If one does not know x, one cannot inquire about x.

- C

- Therefore, one cannot inquire about x.

Two Solutions to the Paradox

- Plato

- “learning” (mathēsis) is “recollection” (anamnēsis)

- Aristotle

- all “inquiry” (zētēsis) is a “search for the “middle term”:

-

Inquiry begins with prior knowledge of the “that” (hoti), some universal fact.

-

From there the inquirer seeks to know the “why” (dihoti), the explanation of that universal fact.

-

The why is given by the middle term of a demonstration of the fact known.

-

The Structure of a Demonstration

- “Why?” Question

- Why are all S’s P?

- Demonstrative Explanation

- Because M!

| Major Premise | All M are P |

|---|---|

| Minor Premise | All S are M |

| Conclusion | So, all S are P |

An Example

- The “That”

- The moon is eclipsed.

- “Why?” Question

- Why is the moon eclipsed?

- Demonstrative Explanation

- Because the earth is interposed between it and the sun!

| Major Premise | Everything the earth is interposed between is eclipsed |

|---|---|

| Minor Premise | The earth is interposed between the moon |

| Conclusion | So, the moon is eclipsed |

The Indemonstrability of Principles

-

For some demonstrations it will be possible to ask “why?” even about the premises, e.g.:

-

“Why?” Question: Why do broad-leafed plants shed their leaves?

-

Explanation: M = their sap coagulates at the stem of the leaf

-

-

However, on pain of an infinite regress, there must be demonstrative premises about which one cannot coherently ask “why?” (APo 1.3). these “first principles” will therefore be “immediate” because “unmiddled”; there is no middle term explaining the connection between subject and predicate.

-

Three kinds of first principle:

-

Axioms: For all p, p or not-p.

-

Posits: A triangle is a three-sided closed plane figure.

-

Definitions: A human being is a rational animal.

-

Metaphysics Z.17’s “Fresh Start” Revisited

- Proposal

- Substance can be understood as the cause of being.

- Objection

- Causal explanations are explanations of why some predicate belongs to some subject per se and in virtue of its essence, but to say that (e.g.) a human being is a rational animal is not a predication but a definition!

- Revision

- Definitions can be understood as a kind of predication and as a subject of scientific inquiry:

Metaphysics Z.17, 1041a22–b32 (Ross tr.)

… that it is predicable must be clear; for if not, the inquiry is an inquiry into nothing. [25]

- E.g. why does it thunder?—why is sound produced in the clouds?

Thus the inquiry is about the predication of one thing of another.

- And why are certain things, i.e. stones and bricks, a house?

Plainly we are seeking the cause. And this is the essence (to speak abstractly), which in some cases is that for the sake of which, e.g. perhaps [30] in the case of a house or a bed, and in some cases is the first mover; for this also is a cause. But while the efficient cause is sought in the case of genesis and destruction, the final cause is sought in the case of being also.

Example: Substance as the Cause of Being of a House

- The “That”

- This configuration of stones and bricks is a house.

- “Why?” Question

- Why is this configuration of stones and bricks a house?

- Demonstrative Explanation

- Because they are a shelter for persons and their possessions (= SHELTER)!

| Major Premise | Every SHELTER is a house |

|---|---|

| Minor Premise | This configuration of stones and bricks is a SHELTER |

| Conclusion | So, this configuration of stones and bricks is a house. |

Metaphysics Z.17, 1041b6–8

…Clearly the question is why the matter is some individual thing, e.g. why are these materials a house? Because that which was the essence of a house is present. And why is this individual thing, or this body in this state, a man? Therefore what we seek is the cause, i.e. the form, by reason of which the matter is some definite thing; and this is the substance of the thing.

Two Causes of Being

- “That for the sake of which”

- E.g., why is this configuration of wood a bed? Because it is a platform for lying on, and this (say) is what it is to be a bed. Why is this configuration of flesh and bones (or an animal of such and such a sort) a human being? Because it is a rational animal, and this is just what a human being is.

- “The first mover”

- E.g. why is this configuration of flesh and bones (or an animal of such and such a sort) going to be a human being? Because it is the production of a rational animal, and this is just what a human being is.

Questions Arising

-

How does Aristotle’s extension of the Analytics model to explanations of the being (as opposed to per se attributes) of substances account for the “indemonstrability” of definitions?

Relevant text from Posterior Analytics 2.10 (93b36–94a12):

Thus one definition of definition is the one stated; another definition is an account which makes clear why a thing is. Hence the former type of definition signifies but does not prove, whereas the latter evidently will be a sort of [94a1] demonstration of what a thing is, differing in position from the demonstration.

For there is a difference between saying why it thunders and what thunder is; for in the one case you will say: Because the fire is extinguished in the clouds. What is thunder?—A noise of fire being extinguished in the clouds. Hence the same account [5] is put in a different way, and in this way it is a continuous demonstration, in this way a definition.

Again, a definition of thunder is noise in the clouds; and this is a conclusion of the demonstration of what it is.

The definition of immediates is an undemonstrable positing of what they are. [10] One definition, therefore, is an undemonstrable account of what a thing is; one is a deduction of what it is, differing in aspect from the demonstration; a third is a conclusion of the demonstration of what it is.

- What about simple essences?

Metaphysics Z.17, 1041b9–10 (Ross tr.)

Evidently, then, in the case of simple things no inquiry nor teaching is possible; but we must [10] inquire into them in a different way.

Of what sorts of substances are the essences simple?