Introduction

Hylomorphism defined

- Hylomorphism

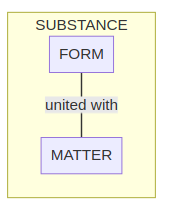

- The metaphysical theory that a substance is a composite of “form” (morphē, eidos) and “matter” (hulē).

Parsing the definition

Hylomorphism posits a relationship between three items: substance, form, and matter.

Substance (ousia)

Comes from the from the Greek “to be” (einai):

-

Prior to Aristotle, has a variety of meanings:

-

“Property”, or “that which is one’s own”

-

“Being”, “reality”, “existence” (to on) - Charles Kahn

-

-

Both senses seem to be at work in Aristotle’s conception of substance:

(1) Substance as essence

-

For Aristotle, the ousia of a thing is identical to “what it is” (ti esti) or, as it’s sometimes known, it’s essence.

-

The “what it is” corresponds to a thing’s definition (horos, horismos, lit. “limits”, “boundaries”), or what we know when we know what something is, it’s essence.

-

The association between ousia, ti esti, and definition precedes Aristotle. Recall:

-

Socrates (in the Platonic dialogues at least) famously traces disputes about the status of some action as virtuous, or the properties of a given virtue, to questions about what that virtue is:

Plato, Meno 70a–b

MENO: Can you tell me, Socrates, can virtue be taught? Or is it not teachable but the result of practice, or is it neither of these, but men possess it by nature or in some other way?

SOCRATES: …I myself, Meno, am as poor as my fellow citizens in this matter, and I blame myself for my complete ignorance about virtue. If I do not know what something is, how could I know what qualities it possesses? Or do you think that someone who does not know at all who Meno is could know whether he is good-looking or rich or well-born, or the opposite of these? Do you think that is possible?

-

Plato famously follows Socrates in thinking of the objects of knowledge as corresponding to the “what it is”, or essence, of what we know—with one major difference.

Plato, Phaedo 70b–c

Then before we began to see or hear or otherwise perceive, we must have possessed knowledge of the Equal itself if we were about to refer our sense perceptions of equal objects to it, and realized that all of them were eager to be like it, but were inferior.

That follows from what has been said, Socrates.

But we began to see and hear and otherwise perceive right after birth?

Certainly.

We must then have acquired the knowledge of the Equal before this.

Yes.

It seems then that we must have possessed it before birth.

It seems so.

Therefore, if we had this knowledge, we knew before birth and immedi- ately after not only the Equal, but the Greater and the Smaller and all such things, for our present argument is no more about the Equal than about d the Beautiful itself, the Good itself, the Just, the Pious and, as I say, about all those things which we mark with the seal of “what it is,” both when we are putting questions and answering them. So we must have acquired knowledge of them all before we were born.

-

-

Here’s how Aristotle characterizes the difference:

Aristotle, Metaphysics A 6, 987a28–b12

After the systems we have named came the philosophy of Plato, which in most respects followed these thinkers, but had peculiarities that distinguished it [30] from the philosophy of the Italians. For, having in his youth first become familiar with Cratylus and with the Heraclitean doctrines (that all sensible things are ever in a state of flux and there is no knowledge about them), these views he held even in later years. Socrates, however, was busying himself about ethical matters and [987b1] neglecting the world of nature as a whole but seeking the universal in these ethical matters, and fixed thought for the first time on definitions; Plato accepted his teaching, but held that the problem applied not to any sensible thing but to entities [5] of another kind—for this reason, that the common definition could not be a definition of any sensible thing, as they were always changing. Things of this other sort, then, he called Ideas, and sensible things, he said, were apart from these, and were all called after these; for the multitude of things which have the same name as the Form exist by participation in it. Only the name ‘participation’ was new; for the [10] Pythagoreans say that things exist by imitation of numbers, and Plato says they exist by participation, changing the name. But what the participation or the imitation of the Forms could be they left an open question.

(2) Substance as “what is”

-

to on in Presocratic thought

- Aristotle’s testimony alludes to a distinction that occupied Plato as well as Presocrates like Parmenides, Melissus, Empedocles, Anaxagoras, and Democritus: the distinction between “what is” (to on) and “what is not” (to mē on).

-

Parmenides and his Eleatic “school” famously challenged the possibility of change (or “coming to be”) on the grounds that it is impossible for there to be anything except to on:

-

A quick & dirty version of the Eleatic argument:

-

Parmenides: not only is it impossible for to mē on to be, it is impossible to think or even say to mē on.

-

If what-is “came to be” (ginesthai), it previously was not.

-

What is not cannot be.

-

Therefore, what-is did not come to be.

-

Therefore, coming to be (change) is impossible.

-

-

The ontological theories of the so-called Eleatic pluralists—Empedocles, Anaxagoras, Democritus—are often read as attempts to explain change in a way consistent with Eleatic principles:

-

Empedocles argued that what-is (the four elements) exists in an eternal cycle of combination and separation governed by the causal principles Love and Strife.

-

Anaxagoras argued that “all is in all”, and that the macroscopic differences in things are brought about by alternating shifts in the preponderance of some properties over others in different portions of the cosmic mixture, the changes being brought about and ordered by Nous (mind).

-

Democritus (and Leucippus) argued that to on and to mē on both equally are: to on are indivisible (atomic) bodies, to mē on is the void through which they travel, combine, and separate with one another. Macroscopic change is just the combination and separation of unchanging microscopic atoms.

-

-

- Aristotle’s testimony alludes to a distinction that occupied Plato as well as Presocrates like Parmenides, Melissus, Empedocles, Anaxagoras, and Democritus: the distinction between “what is” (to on) and “what is not” (to mē on).

-

to on in Plato

-

Plato picks up on this distinction, dividing the objects of cognition between coming-to-be (genesis), which we apprehend by means of the senses, and what is (ousia), which we apprehend by thought. (Republic 7, 534a)

-

More strikingly, Plato seems to have ontologically separated the objects of perception and the objects of thought, and reserved the designation “real being” (to ontōs on) for the objects of thought:

Plato, Timaeus 52a–b

Since these things are so, we must agree that that which keeps its own form unchangingly, which has not been brought into being and is not destroyed, which neither receives into itself anything else from anywhere else, nor itself enters into anything else anywhere, is one thing. It is invisi- ble—it cannot be perceived by the senses at all—and it is the role of understanding to study it. The second thing is that which shares the other’s name and resembles it. This thing can be perceived by the senses, and it has been begotten. It is constantly borne along, now coming to be in a certain place and then perishing out of it. It is apprehended by opinion, which involves sense perception. And the third type is space, which exists always and cannot be destroyed. It provides afixed state for all things that come to be. It is itself apprehended by a kind of bastard reasoning that does not involve sense perception, and it is hardly even an object of conviction. We look at it as in a dream when we say that everything that exists must of necessity be somewhere, in some place and occupying some space, and that that which doesn’t exist somewhere, whether on earth or in heaven, doesn’t exist at all.

-

This distinction is a central component of Plato’s “Theory of Forms”, so called because he reserved the word eidos, form, for the real beings apprehended solely by thought…

-

Aristotle on substance

- Question

- What is a substance in Aristotle’s theory?

- Answer

- Depends on where you look!

-

Categories: Substance is:

-

In the strictest sense, what is “neither said of nor present in a subject” (2a11–13)

-

“A certain this” (tode ti), i.e., something “indivisible” and “numerically one” (3b10–11).

-

-

Metaphysics Z: The substance of a thing (e.g. some tode ti) could be:

-

Essence

-

A “universal”

-

The genus

-

The subject of predication

-

The “cause of being” (Z 17)

-

-

Observation: Matter and form play a significant role of Aristotle’s discussion of substance in Metaphysics Z, but not in Categories.

-

The Puzzle: How do the Categories and Metaphysics Z accounts of substance relate? Do Aristotle’s views on substance develop? If so, how does the introduction of hylomorphism influence the development of Aristotle’s views?

-

Form (morphē, eidos)

-

Aristotle has two words for form:

-

Eidos (lit., “look”), which comes from the (related) Greek words “to see” (oida) and “to know” (eidenai).

-

Morphē, which means “shape” or “appearance”.

-

-

What is distinctive about Aristotle’s conception of form?

-

Towards an answer:

-

Recall what Aristotle says of Plato’s reception of Socrates:

-

Socrates was the first to draw attention to definitions.

-

Plato, however, was convinced that the sensible world was in a state of constant flux and change, which meant that what definitions define could not be anything sensible.

-

Hence the objects of definition must be separate from the mutable objects of perception and, unlike them, imperceptible, stable, unchanging, fully what they are, etc. etc.

-

-

Aristotle famously denies that that forms are separable in the way Plato claimed (see On Ideas):

-

To say that forms are separable from sensible “particulars” implies that forms could be without sensibles (Metaphysics Δ 11)

-

To the contrary, Aristotle believes that nothing would be without “primary” substances:

Aristotle, Categories 5, 2a35–b5

All the other things are either said of the primary substances as subjects or in [35] them as subjects. This is clear from an examination of cases. For example, animal is predicated of man and therefore also of the individual man; for were it predicated of none of the individual men it would not be predicated of man at all. Again, colour is [2b1] in body and therefore also in an individual body; for were it not in some individual body it would not be in body at all. Thus all the other things are either said of the primary substances as subjects or in them as subjects. So if the primary substances [5] did not exist it would be impossible for any of the other things to exist.

-

-

Aside: (little “p”) platonic vs. (little “a”) aristotelian theories of universals

- Universal

- What is “said of” many things, e.g. redness, “human being”

- Particular

- What is not “said of” many things, e.g. scarlet, this scarlet letter, Socrates

- Question

- Would scarlet exist if nothing were scarlet colored?

-

(Little “p”) platonic response: Yes! Universals are not ontologically dependent on their particular instances.

-

(Little “a”) aristotelian response: No! Universals depend on their particular instances.

-

Controversies over Aristotle’s theory of form

-

Are Aristotelian forms particular or universal?

-

If form corresponds to the essence and definition of a thing, is it also the substance of that thing?

-

Is form always the form of some matter?

Matter (hulē)

-

Literally means “wood” or “stick”, but Aristotle associates it with two features of particulars:

-

The “subject” or “substratum” (hupokeimenon) of which properties are predicated. (Aristotle associates substance with this too.)

-

“That from which” (to ex hou): most intuitively, the materials from which an object (Socrates or a chair) is fashioned or comes to be.

-

-

Aristotle associates matter (or the “material cause”) with the theories of the earlier Ionian “natural philosophers” (phusiologoi): Thales (everything is [from] water), Anaximander (everything is from the “unlimited”, apeiron), Anaximenes (everything is [from] air):

Aristotle, Metaphysics A 3, 983b5–19

Of the first philosophers, most thought the principles which were of the nature of matter were the only principles of all things; that of which all things that are consist, and from which they first come to be, and into which they are finally [10] resolved (the substance remaining, but changing in its modifications), this they say is the element and the principle of things, and therefore they think nothing is either generated or destroyed, since this sort of entity is always conserved, as we say Socrates neither comes to be absolutely when he comes to be beautiful or musical, [15] nor ceases to be when he loses these characteristics, because the substratum, Socrates himself, remains. So they say nothing else comes to be or ceases to be; for there must be some entity—either one or more than one—from which all other things come to be, it being conserved.

-

No clear Socratic or Platonic precedent—although compare Plato’s notion of “space” (chōrē) in Timaeus.

-

Aristotle often speaks of matter as a relative term: all matter is the matter of something:

-

The matter of the chair is wood

-

The matter of the wood is earth

-

However, the matter of the chair is not earth.

-

matter is the potential for form, which, in turn, is that actualization of some material potential.

-

Questions for Unit 1

-

How does Aristotle understand being and substance in the Organon?

-

Is this a framework within which we can make senses of a hylomorphic analysis of substance?